Three Methods for Outlining Your Book

The secret to self-publishing success on Amazon boils down to three steps:

- Write

- Sell

- Repeat

Each of those steps has a lot of other stuff going on (and you’ve read hundreds of articles here about the details of that stuff), but that’s the basic gist. Another important point is that, the faster you can repeat the cycle, the more money you will make. As long as the quality is good, each new book in your catalog is a new income stream for your writing career.

Outlining is one of the best tools to keep your writing on track, your completion schedule faster, and your catalog adding new books on a regular basis. It helps you to write just what’s necessary to tell your story, and it helps you set benchmarks so you stick to your writing schedule. If you use ghostwriters, an outline is vital to keep the project heading in the direction you want.

Bottom line: you should try outlining your book. The only question is how. Below you’ll find the three of the best methods for this task.

- The Roman Numeral Outline. You learned this in middle school.

- The Mind Map, for the more visual and creative of us.

- Story Engineering, which adds pace to your structure

One of these, or a variation you devise from the basics you learn today, will work for you.

Outlining vs. Pantsing

In professional writing circles, an outliner is somebody who uses outlines to structure their book, and who knows how he plans to get from point A to point B. A pantser (otherwise known as a discovery writer) flies by the seat of their pants, following the story as it progresses with little idea about what’s going to come next.

You can get into all kinds of arguments about which way is better when you’re talking about the art and craft of writing. It really depends on your own personality and skills.

For our purposes, though, it is well worth outlining to see how well it can work for you as it can help you more efficiently find your story and get it down on the page. Pantsers sometimes feel happier about their writing process, but unless they've internalized solid story structure it can lead to consistently writing fewer books.

This is not sacrificing quality for quantity. Many of the best authors in the world outline for every book. Instead, good outlining mojo lets you turn out a quantity of quality writing. It’s the best of both worlds.

The Roman Numeral Outline

You know this one. Like we said, it’s what you learned in middle school. Heck, there’s a button for it in your word processor. A Roman Numeral Outline might look like this:

- Introduction

- Hook

- Preframing

- Outlining vs. Pantsing

- Roman Numeral Outline

- Introduce and define

- Example [you’re reading this right now]

- Detailed description

- Mind Map

- Introduce and define

- Example

- Detailed description

- Story Engineering

- Introduce and define

- Example

- Detailed description

- Let’s Get Started

- Final note (flexibility in planning)

Seem familiar? We thought so. Here’s how to put it to work.

Start with a general idea of how long your book will be, in chapters. Make a roman numeral for each chapter in the book. From there, write a brief note for I about the opening scene, and a brief note for your last numeral for how you want it to end.

For example, if you’re writing a kid’s book about a fifth grader who learns how to fight from a ninja, your entry I might be him waking up on a normal day. Your final entry could be him going to bed after his first adventure, and seeing his bedroom changed from his perspective.

With your bookmarks in place, think about any particular scenes you already have in mind. Put them in the middle. One nice thing about doing this in Word or a similar program is you don’t have to worry which Roman numeral you assign to the middle parts. They’ll change as you add, delete, and move components of the story.

For example, you know you want the story to climax with a food fight in the cafeteria. You enter “Food Fight!” above the final entry. Even though you don’t know what they’ll be like yet, you also enter Bullied by the Villain, Meet the Ninja, Pass the Test, and Save the Dog in your outline. You know where they’ll go even if you don’t know what they’re like.

With these basic linchpins of your story in place, keep adding connective tissue until you have the basic story progress lined out. It’s okay to put something like “pacing action” or “?” if you have two entries that need something in between them, but you’re not sure what they are yet.

For example, you know your hero will wake up and have a boring day at home before he walks to school and gets bullied along the way. Between “Wake Up” and “Bullied by the Villain”, you put “Breakfast with Dad”, “Feed the Dog” and “Walk Halfway to School.”

At this point, each entry on your outline is a scene for your story. Some people like to stop when they have all (or most) of their scenes listed, then start writing. Others go in another level and add some details, action, or character and story notes for each. It’s up to you.

The Mind Map

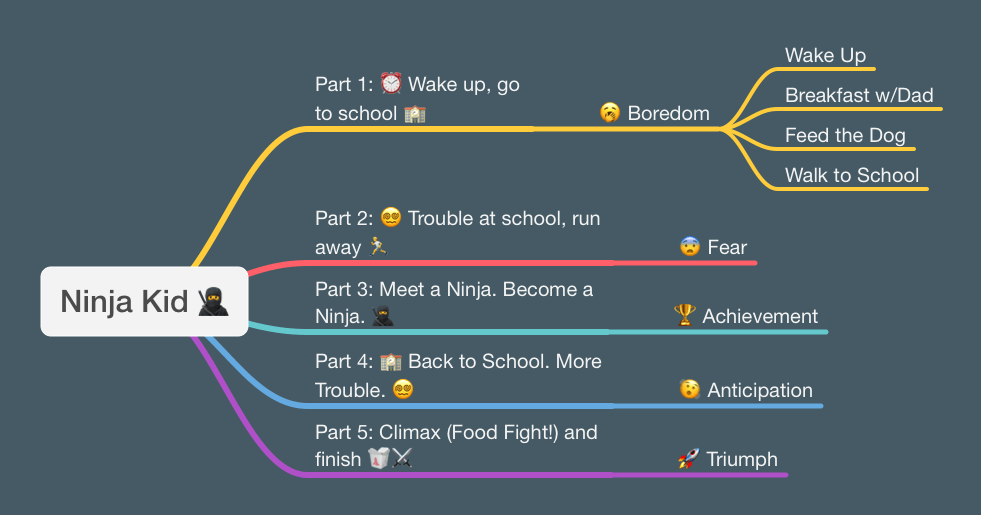

Mind maps are for the visual and creative writers among us, letting us write down our stories in a more free-form way before we commit to a final outline. You may also have seen this in school. A mind map looks like this:

Start a mind map by drawing a circle at the center of the document and writing the name of your book in the middle. Draw a straight line leading away from it, ending with a circle about halfway to the edge of the page. Label that circle Part One. Do the same thing for Last Part a little bit to the left. Add other parts (think acts in a play) in between them. How many Parts your book has will depend on the length and its complexity. Once they’re all in place, add a short description of the main action of each part.

For example, with our ninja kid book, we decide it has five parts. We draw a five lines and circles out from our center circle. We label the parts as follows:

Part One: Wake up, go to school

Part Two: Trouble at school, run away

Part Three: Meet a ninja. Learn how to ninja

Part Four: Back to school. More trouble

Part Five: Climax (food fight) and finish

The next part of the mind map process depends on you. Add additional circles and lines coming off of each of your parts with further details. Some people like to make a circle for each scene or chapter in that part. Others prefer to be more freeform. They might add a circle each for story goals, character goals, emotional notes, and similar details they want to accomplish in that part, but leave the detailed progress of the scenes for their writing sessions. There’s no wrong way to do this, as long as it works for you.

For example, we decide that we want to elicit different emotions with each part of our ninja book, with Boredom as the emotion for Part One, Fear for Part Two, Curiosity and Accomplishment for Part Three, Anticipation for Part Four, and Laughter and Triumph for Part Five. After noting that with its own circle, we add details as branches off of those circles with ideas for how we will bring those emotions onto the page.

Finally, spend some time adding any other details you can brainstorm. Some parts will only have sparse notes, while others will have long strings of circles and lines as you get more and more details for scenes, characters, action sequences, and even whole paragraphs you want to put into your story.

Note

More than one author likes to start with a Mind Map because it’s freeflowing and visual, then transcribe the information into a classic Roman numeral outline before they begin writing.

Story Engineering

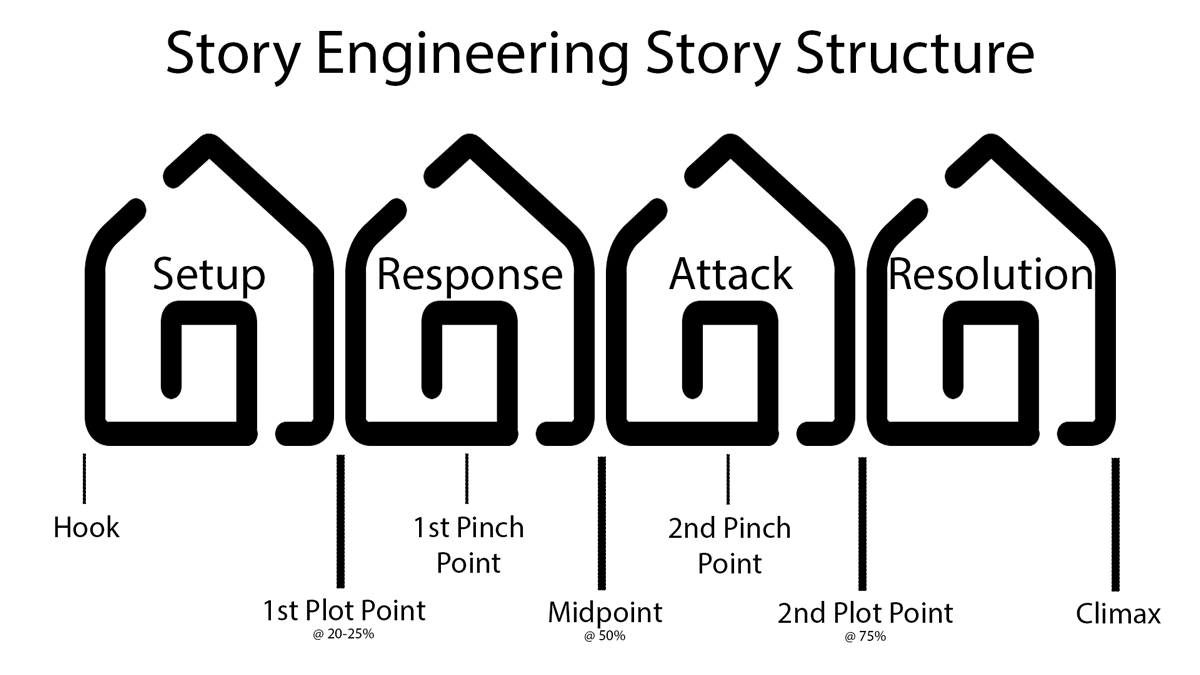

Story Engineering (a term introduced by author and speaker Larry Brooks), takes the rough concept of an outline and builds the story from its most pivotal points, filling in the connective tissue piece by piece. A story engineering diagram looks like this:

Story engineering identifies the key parts of a blockbuster book’s plot:

- The setup, which begins with establishing the status quo and ends with the protagonist’s first major encounter with something that changes everything

- The response, in which the protagonist…well, uh…responds to that encounter. In a short book this happens one time. In longer stories, it happens in a cycle of attempt and failure, or solutions and new problems.

- The attack, where the protagonist figures enough things out to move forward and confront the antagonist.

- The resolution, which features the leadup to the climax, the climax itself, and any after action like a denouement or a prologue.

Take a sheet of paper (or a whiteboard, which is what I usually use), and divide it into four sections. In each, write one or two sentences about what happens.

For example, our ninja kid’s story might go on the board thusly. The setup runs from him waking up and having a boring day, getting bullied, and having a weird encounter with the ninja. The response includes his meeting with and formally training in ninja skills, ultimately becoming a ninja master. The attack sends him back to school, standing up to the bully and finding out he’s “dead meat at lunch.” The resolution leads our nervous, but ready kid to the cafeteria, into a hilarious ninja food fight, and back home with a new outlook on life.

Story engineering also identifies a key scenes at the beginning, middle, and end of each part of the book. These include:

- The hook, which are the first sentences of the story and responsible for drawing you in

- Inciting incident, the first action after the hook that establishes some kind of initial problem

- The first plot point, where the status quo you introduce gets changed. This forms the transition from setup to response

- The first pinch point, a challenge or problem introduced halfway through the response, which raises the stakes

- The midpoint, a scene where something changes or falls into place to let the protagonist take control of the action. This serves as the transition between the response and the attack.

- The second plot point, which happens halfway through the attack and sets the story on its final course toward the climax

- The climax, which wraps everything up with tension and a general sense of awesomeness.

On your whiteboard, write a brief description of each of these points in the book. From our examples so far, we might see each of these as:

Hook: a funny scene of waking up in a weird position and being just sooooo bored

Inciting incident: getting bullied on the way to school

First Plot Point: meeting the ninja in a janitor’s closet

First Pinch Point: the ninja promises to teach our kid if he passes a difficult riddle or physical challenge

Midpoint: our kid finishes his ninja training and prepares to return to school

Second Plot Point: a confrontation with the bully which leads toward the lunchtime confrontation

Climax: the big ninja food fight and ultimate victory

Those seven points will give you the skeleton of your story from start to finish. Your next task is to add the muscle and flesh and connective tissue, either by expanding the outline or beginning to write.

Let’s Get Started

Give this a try with your newest work, or even with your current work in progress. Get a blank art pad (I recommend the ones at your local dollar store), open it up and start with that first point. From there, you just fill in the blanks until your outline is ready.

One Last Important Note

Always remember that your outline is a starting point. You won’t finish the outline with every single detail and inspiration already fully formed in your mind. While you’re writing, if you suddenly get a great idea, you should follow it. It’s okay to change the plan, but changing an existing plan is always better than trying to move forward without a plan in the first place.

An outline is a tool, not a straitjacket. Use it to get started, then see how far you can go.